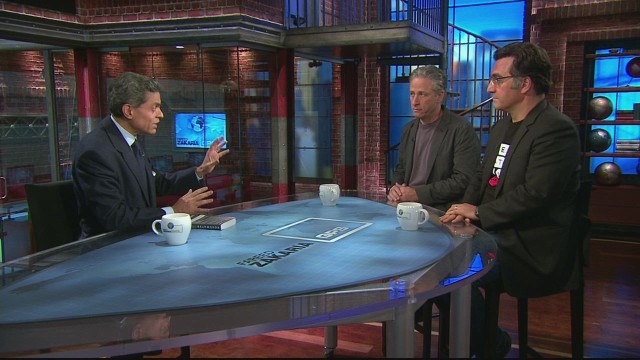

Jon Stewart & Maziar Bahari on Fareed Zakaria GPS

CNN’s FAREED ZAKARIA GPS features an interview with Jon Stewart and Iranian-born journalist Maziar Bahari to discuss Iran, the Arab Spring, and their new film Rosewater. In 2009 Maziar Bahari was arrested under the pretext of espionage following the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and the Green Revolution. The film Rosewater depicts the 118 days of Bahari’s mental and physical torture under the Iranian regime. Jon Stewart, director of Rosewater, tells Fareed Zakaria that he feels many people are trapped between authoritarianism and religious extremism. He points to the Iranian regime’s shortsighted approach to retaining power. Both Bahari and Stewart describe the rationality of the Iranian regime’s irrationality, which was fundamental to Bahari’s detention after the Green Movement. Text excerpts and a full interview transcript are available below.

TEXT EXCERPT

Stewart on torture in Iran: “I think there is a rationality behind it. And to view it in that way means it can be manipulated. And it means that you can fight back against it. And so there is a banality to it. There is a — I would consider it more the bureaucracy of evil and the stupidity of evil.”

Stewart on the Arab World: “this is a part of the world that has been trapped between authoritarianism and extremism. And it’s very difficult for the majority of the people who live there, who are just looking to carve out a little space for themselves and to live their lives, to get that space and create those civic institutions when you are constantly trapped between those two poles.”

Bahari on his experience in solitary confinement: “your only way to communicate with the rest of the world is through your interrogator. But when my interrogate — my — one of the prison guards, by mistake, called me Mr. Hillary Clinton, there and then I realized that there is a campaign for me. So I — that was the best moment for — for a prisoner, the worst thing is to think that he or she is alone. And that was a moment that I realized that I was not alone.”

Bahari on the principles and outcomes of the 2009 Green Movement: “It was a movement of millions of Iranians to gain their rights as citizens of the country. They did not want to be the subjects of the master, the supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei. So the movement continues. You may not see the manifestations of the movement on the streets, but the people’s demand to be considered as citizens of the country continues.”

A full interview of the transcript is available after the jump.

FULL INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

THIS IS A RUSH TRANSCRIPT. THIS COPY MAY NOT BE IN ITS FINAL FORM AND MAY BE UPDATED

FAREED ZAKARIA, HOST: Tehran, June 21, 2009. The city is in tumult following the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and The Green Revolution that followed.

On that day, Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-Canadian reporter for “Newsweek,” was taken from his mother’s house, arrested and thrown in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison. He would be held there for 118 days in solitary confinement. He wrote a terrific book about the ordeal. That book has now been turned into a movie called “Rosewater.” The title comes from the perfume that Bahari’s interrogator used.

This was a story I was intimately familiar with because I was, at the time, the editor of “Newsweek International” and got deeply involved in the campaign to free Bahari. I read the book, and still the movie was able to shock me, move me. It is a powerful, intelligent film.

Joining me now are Maziar Bahari and this other guy, the writer and director on the project, an unknown first time filmmaker by the name of Jon Stewart.

JON STEWART, DIRECTOR, “ROSEWATER: Nice to see you.

MAZIAR BAHARI, AUTHOR, “ROSEWATER”: Nice to be here.

ZAKARIA: So when you look at it now, what do you think of The Green Revolution? Did it fail? Did it succeed?

BAHARI: Well, I think if we think of it as a revolution, it failed. But it was never a revolution. It was a Green movement. It was a movement of millions of Iranians to gain their rights as citizens of the country.

They did not want to be the subjects of the master, the supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei.

So the movement continues. You may not see the manifestations of the movement on the streets, but the people’s demand to be considered as citizens of the country continues. And the fact that Rouhani was elected last year was a direct result of the demonstrations in 2009. Without those..

ZAKARIA: You don’t think he’s — you don’t think he’s a great liberal?

BAHARI: I don’t think he’s a great liberal. No, no, no. I mean when Rouhani was elected, people said that you shouldn’t judge him, you should — you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. But you should always judge the book by its grammatical errors…

(LAUGHTER)

BAHARI: — you know lack of plot and, you know, mistakes. And I think he’s done a — he’s done many mistakes now. And I don’t think he’s a liberal. But he’s better that Ahmadinejad, which is a great step forward.

I mean Iranians, they look at any kind of sudden change with trepidation now. They do not want a repeat of 1979 revolution. When they are — when they are looking at that neighborhood, when they see what the Syrians are doing, for example, or what happens in Iraq or Afghanistan, they don’t want a repeat of that. That’s why the pace of reform, pace of change in Iran is very slow, excruciatingly slow.

But that means that it’s sustainable.

STEWART: Right.

BAHARI: If the outsiders don’t interfere, of course. If there is an attack, if there is any kind of bombing, that’s going to interrupt that pace of change. But if they just let the change to take its path, it’s going to be a sustainable change and sustainable reform.

ZAKARIA: So you filmed this mainly in Jordan, around Amman.

STEWART: That’s right. That’s right.

ZAKARIA: So you spent six weeks in the Arab world, as it were…

STEWART: About ten weeks.

ZAKARIA: And this was at a pretty interesting time of — in terms of the — what was going on in the Arab world.

STEWART: Right.

ZAKARIA: Again you’re a student…

STEWART: Is there ever not an interesting time when things are going on in the Arab world?

ZAKARIA: You’re a — you’re a close student of this kind of stuff.

STEWART: Yes.

ZAKARIA: What’s your impression? A 10 — you know, 10 weeks in the Arab world. Did it change the way you think about the Middle East?

STEWART: Well, I think, you know, there are – there are moments whenever you immerse yourself with a people and a culture — and this is in no way to suggest that filming a movie in a — in a city is in any way akin to… to living there…

ZAKARIA: Sure.

STEWART: — or being a part of it, because there’s a very self-selecting group of people that you end up interacting with at all times.

That being said, you can get a feel for the flavor and character of a place. And there are moments of great hope within it. You sense the humanity of the people there, the great hospitality of the people there. But you also see the obstacles and the barricades that are up that prevent that sort detente that we’re hoping for.

So there were moments of great hope followed by just feelings of like, well, this is — this is going to take — this is going to be a long cultural shift. You know, this is a part of the world that has been trapped between authoritarianism and extremism. And it’s very difficult for the majority of the people who live there, who are just looking to carve out a little space for themselves and to live their lives, to get that space and create those civic institutions when you are constantly trapped between those two poles.

ZAKARIA: You’re not hopeful on an Iranian deal? I just…

BAHARI: I don’t think so. I don’t think that there will be a deal on the 24th of November, because I don’t think that there is a real will, either in Iran or the United States, to have a deal on the 24th. And there are also radical interest groups in both countries, in Iran, the Revolutionary Guards are making a lot of money because of the sanctions and because of there is no relationship between Iran and the United States.

And in this country, as you know, there are many lobbies for making a lot of money by supporting the sanctions and not having…

STEWART: Right.

STEWART: Not a lot of incentives on either side.

ZAKARIA: And fair to say that whatever deal Obama were to bring, it would be pilloried…

STEWART: Hugely popular. Whatever he does…

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: — my feeling is it will be hugely popular and hailed throughout our political system.

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: That’s my favorite is the — the new climate deal. So all they talk about in Congress is we can’t — we’re not going to do a climate deal, because if we don’t get China on board, it’s meaningless.

ZAKARIA: Yes.

STEWART: It’s utterly meaningless.

OK, we’ve got China on board. No deal.

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: China. No.

ZAKARIA: Yes. It’s a foreign country…

STEWART: It’s something else.

Why would we allow the United Nations and China to decide our economy?

So you realize the system right now is incentivized for status quo, for stagnation. You don’t raise money on bipartisanship, on cooperation and good governance. You raise money on demonization. And that’s — that’s where we sit.

ZAKARIA: Next on GPS, I will tell you about the role that this show, GPS, played in Maziar’s story and thus the movie. It was sort of pivotal, when we come back with Maziar Bahari and Jon Stewart.

ZAKARIA: And we are back with Maziar Bahari, the writer of the book “Rosewater,” and Jon Stewart, the writer/director of the film, “Rosewater.”

About six weeks after you were thrown in a prison, Maziar, I interviewed then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in Kenya, of all places. I asked her about you.

Let’s watch the clip.

ZAKARIA: In the movie, the way you present it, and, to a certain extent, in the book…

STEWART: Sure.

ZAKARIA: — is that this was the sort of pivotal moment for you personally, because you suddenly realized, hey, I’m not alone. There are people who actually care about me.

BAHARI: It was the…

STEWART: Right.

BAHARI: — best day of my imprisonment. I mean I cannot say best day maybe because there were not other good days, that it was the best one. It was the only good day of my imprisonment because when they put you in solitary confinement, they deprive you of all your senses. You become delusional and you become suicidal. But because you don’t think that — you don’t know what’s going on outside. And your only way to communicate with the rest of the world is through your interrogator.

But when my interrogate — my – ” there and then I realized that there is a campaign for me.

So I — that was the best moment for — for a prisoner, the worst thing is to think that he or she is alone. And that was a moment that I realized that I was not alone.

ZAKARIA: The certainty of — of the truth, I mean what — what you portray a lot is these guys who, they think they know the truth, but you — you’re always wondering, when watching the movie, are these interrogators really –they seem, at some level, very insecure. It’s a very deft way of portraying it. They seem — there’s a lot of bravado, but they’re very insecure.

STEWART: Right. Well, you also have to portray it within, you know, they’re — they’re human beings. People that are interrogators or torturers, this is a job.

You know, these are not — it’s not something that we might see in sort of a more sensationalized cinematic version of it of, you know, the Bruce Willis over the guy, tell me where the bombs are. This guy’s got to come in every day. He’s got to be there by 8:00. It’s a bureaucracy. He has to work within that. The Green movement, to these interrogators, was, in many ways, just a chance to get some over time. You know, the prisons are…

ZAKARIA: Right.

STEWART: — so filled with people, I think that the gentleman who was responsible for Maziar’s torment, in some ways, probably wouldn’t have had an opportunity to deal with someone, you know, a VIP prisoner, more educated, more Western, if it had not been for the overwhelming amount of people that they were trying to filter through this prison at the time.

ZAKARIA: So do you think of it as like, you know, Eichmann in Jerusalem, the banality of evil?

STEWART: I think, you know, to compare them to Eichmann and the Nazi regime, I think, is also a mistake, and the same with comparing them to ISIS. You know, they are not, you know, ISIS is not a state actor and – and they do true depravity.

I think this is different. And I think there is a rationality behind it. And to view it in that way means it can be manipulated. And it means that you can fight back against it. And so there is a banality to it. There is a — I would consider it more the bureaucracy of evil and the stupidity of evil.

But evil is a relatively rare…

BAHARI: Yes, there is a – there’s a rationale behind their irrationality.

STEWART: Right.

BAHARI: And as you know, the Iranian diplomats and Iranian politicians, you have interviewed them several times, they are very logical people. They are very pragmatical people. But they are working for a system that thrives in insecurity. It thrives in being insecure and making people insecure.

So their irrationality is inherent part of the system. They may not think that they are doing it. They are not doing it intentionally. But that is an inherent part of their character.

ZAKARIA: And you capture, also, the mixture of reality to some of their complaints. There’s this moment where the guy had the — “Rosewater” has the — the Maziar character has to admit, yes, the CIA was involved in the coup against Mossadegh…

BAHARI: Yes, yes, sure.

ZAKARIA: — and so…

STEWART: Right.

ZAKARIA: — wait, you’re saying they were involved then but they’re not involved now. It was a very, you know, it’s always struck me that that’s what regimes like this do. They take a few facts, which are…

STEWART: Sure.

ZAKARIA: — uncontestable…

STEWART: Sure.

ZAKARIA: — and then extrapolate.

STEWART: Sure.

BAHARI: They always, all the paranoia that they have, all the conspiracy theories that they have, they are based on some truth. And then they put one and one together and they conclude it’s 11, not two. So they always blow it out of proportion.

STEWART: Right.

ZAKARIA: I want to get one last admission from you.

STEWART: Please.

ZAKARIA: When you — when world historical things like the Green movement are happening, the Arab Spring happening…

STEWART: Yes, yes.

ZAKARIA: — you tune on…

STEWART: Where do I get my news?

ZAKARIA: — you tune on to CNN…

STEWART: You want to know where I get my news.

ZAKARIA: — watch these brave correspondents…

STEWART: I tune –

ZAKARIA: — who are…

STEWART: — here’s what I do…

ZAKARIA: — risking their lives…

STEWART: — I put a — I set a Google Alert for Blitzer. And then…

ZAKARIA: No.

STEWART: — and then I just wait.

ZAKARIA: Say honestly…

STEWART: We have a CNN exclusive tonight, the Empire State Building is blue.

(LAUGHTER)

ZAKARIA: During The Green Revolution, you watched CNN and appreciated the brave reporting the reporters did…

STEWART: Let me tell you something. The reason why I make fun of certain aspects of CNN is to be inspired by the brave reporting is to want more.

ZAKARIA: Good.

STEWART: And so…

ZAKARIA: That’s all I want.

STEWART: — that’s — that’s all it is.

ZAKARIA: You want more CNN?

STEWART: I want more of good CNN. CNN is very similar to the doll Chucky.

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: Sometimes it’s good Chucky, but you really got to watch out for bad Chucky.

ZAKARIA: But we’re all inspired by the good stuff.

STEWART: No question.

ZAKARIA: Next on GPS,

###END###